The two UCT professors at the centre of the debate around the reliability of the 2022 South African census reflect on what has been misreported by the media and others; what the principal concerns with the data are; and make suggestions for how to proceed.

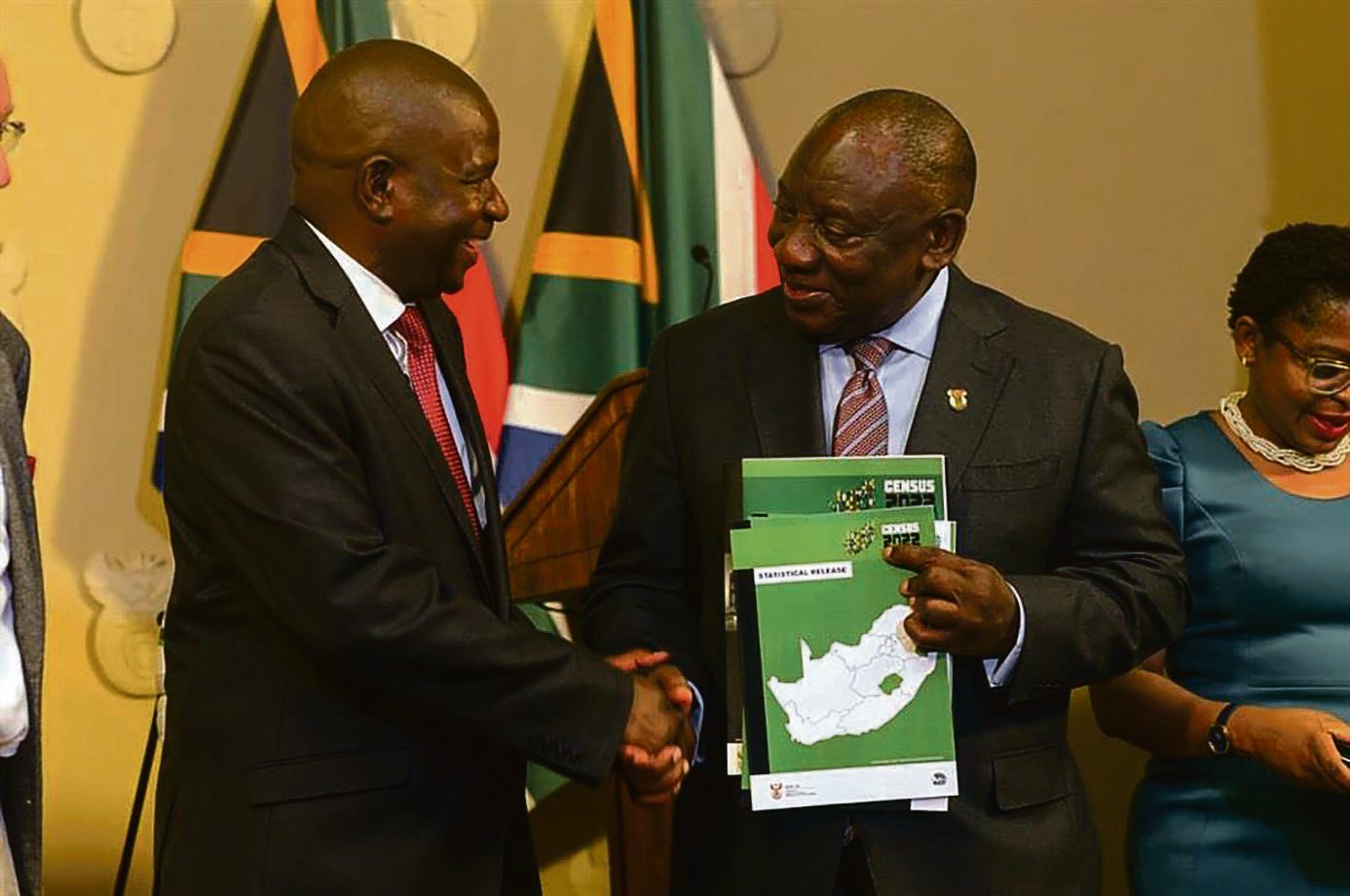

Last week’s announcement by Statistics South Africa (Stats SA) that certain data from the 2022 South African census would not be released re-energised public debate around the fitness-for-purpose of the census.

While it is good that this debate is happening (because the census does matter), much of the commentary and suggestions from journalists, politicians and others has tended to muddy the waters somewhat, and risks losing some of the more serious concerns we raised.

It is important, therefore, to state upfront where we disagree with much of the commentariat’s views on the 2022 Census.

First, we emphatically reject suggestions that the census should be withdrawn or rerun. While we have many serious concerns about the data, and lament that data on fertility and mortality (as well as employment and income) are seemingly to not be made available even to expert evaluation, the suggestion that the census should be rerun is naïve. As we noted in the South African Medical Research Council technical report, the census is the most logistically complex undertaking of a national government in peacetime. Planning for a census takes four to five years (at least), and before this could start there would need to be an analysis of all that went wrong with the current census.

Second, much of the commentary from the general public falls into the category of “I and my friends and neighbours, too, were not counted!”. That does not mean, per se, that the census is an underestimate. Stats SA adjusted for an undercount of 31% overall. However, what sets the 2022 South African census apart is the extent of the reported undercount

So, what are our concerns?

Our early concerns, reiterated

Our first, and primary, concern relates to the estimate of the South African population as of February 2022. Based on our analyses, we think it likely that the reported population estimate of just over 62 million might have been over-corrected by up to a million people (which is entirely consistent with the 61.06 million interpolated from Stats SA’s latest mid-year population estimates). This is on the basis of the broad consistency between projections from past censuses using standard demographic projection methods.

Based on those data, and our detailed knowledge of births and deaths in the country over the period 2011-2022 from other sources, we conclude that the levels of migration required to reconcile the 2011 population with that reported for 2022 stretch credulity.

Importantly, if the implied immigration was correct much of it, proportionally, would have had to have been in the white and Indian/Asian population groups at ages over 50. This defies both demographic and common sense. The extremely high preliminary undercounts reported by Stats SA in those two population groups (62, and 72 percent, respectively) mean that small errors in the estimation of those undercounts would result in significant errors in the estimated population sizes. It appears to us that the adjustment for the undercount probably led to exaggeration of population size of these groups, and hence contributed to an overestimate of the national population size.

READ | Census 2022: Experts warn flawed data could impact big Stats SA surveys, budget allocations

A second concern was that the adjustment for the undercount has distorted the implied patterns of population growth at district and municipal levels in the country, often in defiance of common sense, and often contradicted by the Electoral Commission of SA’s numbers of registered voters over the same period. We expressed concerns that – since municipalities are where the “rubber meets the road” in terms of service delivery and improving the lives of all South Africans – such discrepancies might lead to substantial and significant misallocation of resources in the country.

Both of these concerns, we argue, are a reflection of a third – significant – concern. Anomalous findings such as those described above suggest that the size of the sample of the post-enumeration survey (PES), used to correct the enumerated census population for the undercount, was too small. We have noted that, from the somewhat opaque documentation, it would appear that sample size of that PES was determined based on an assumption that the undercount would be about half of that actually encountered.

We further argued that there must be a mistake in Stats SA’s quantification of the uncertainty surrounding the population estimates, which suggest, for example, that there was little chance that the true population was any more than 120 000 lower or higher than their estimate.

Under the circumstances, and without much more transparency from Stats SA – particularly relating to coverage of the population by the census and the PES – we have serious concerns about the robustness of the adjustment factors used to scale up the actually-enumerated population of around 42 million people (36 million completing the full household questionnaire and 6 million only the far less detailed PES questionnaire) to the final estimate of 62 million. These concerns are amplified by the anomalies in the reported final estimates of subpopulations, whether by population group, age, or for smaller geospatial entities.

Finally, it is important to record that, both in their initial responses to our concerns published in the monograph, as well as subsequently, Stats SA has not once engaged with the substance of our analysis, choosing instead to reiterate repeatedly that they followed the recommended approaches; that they stand by their results; and that the results are “fit for purpose”.

In addition, Stats SA have chosen to assert that they have relied upon (or continue to hide behind?) the opinions of nameless experts and their confidential advice to them and their oversight body, the Statistics Council, on the quality of the census. It is hard to understand how other experts missed such anomalies.

A way forward?

The decision by Stats SA to not make public data on employment, income, fertility, and mortality amplifies our concerns about the fitness-for-purpose of the 2022 Census to guide and assist in the country’s planning and policy development, as well as service delivery. While Stats SA is not wrong to assert that, for example, the Quarterly Labour Force Survey (QLFS) provides the official measures of unemployment in the country, we note that the sample size of that survey is around 66 000 individuals – inadequate to understand labour market dynamics in small areas, or in small populations.

Even though the Census measures of unemployment are not directly comparable to those from the QLFS, the much larger sample allows “drilling down” to small areas, and for economists and others to triangulate the results from the QLFS with other information contained in the census. The decision to not release these data makes that task impossible.

Likewise, the decision to not make public the data on fertility and mortality, and perhaps more detailed data on migration, also compromises demographers’ ability to accurately measure and properly parameterise population projections for the country. This will impact directly on Stats SA’s own set of projections, the mid-year population estimates. And, while the data, may indeed be (as we suspect) highly problematic, we have some experience in salvaging useful estimates from poor data – as we were able to do with the fertility data from the 1996 census.

At the very least researchers should be allowed to attempt such an exercise, although the extent of the undercount, and our concerns about the robustness of the adjustment factors, makes its ultimate success unlikely.

The way forward is fraught and complex:

- Too much time has passed from the collection of the census and the PES to be able to directly rehabilitate the census data collected in 2022 for the undercount.

- Rerunning the census would be worse than pointless. The decision to not run a census every five years, was taken following the 2001 census not least out of concern as to the lasting damage that attempting that exercise might inflict on Stats SA.

- Planning for the next census (scheduled for 2031) must begin shortly. To have a successful census then requires that we, as a country, fully understand what went wrong with the 2022 census. Blaming the extreme undercount on the Covid pandemic as the sole (even if significant) cause is inadequate and denies the possibility that there were internal missteps that contributed to the errors identified. Amongst others, the decision to pursue a digital-first census in 2022 should be evaluated.

- Stats SA should urgently reconsider their decision to not release some parts of the data to the public; or, if not that, to make those data available to researchers able to assess its usefulness.

- Stats SA should cease “doubling-down” on the results of the census, and respond – properly, and in detail – to the concerns we, and – increasingly – others have raised. Doing so would require a degree of openness and commitment to engagement and public scrutiny, that the organisation has resisted thus far.

- In the absence of reliable and credible census numbers, the country needs an agreed-upon alternative set of population estimates to inform policy and planning in the period before the results of the next census are released.

Tom Moultrie is Professor of Demography at the University of Cape Town; Rob Dorrington is Professor Emeritus and Senior Research Scholar in the Centre for Actuarial Research at the University of Cape Town.

News24 encourages freedom of speech and the expression of diverse views. The views of columnists published on News24 are therefore their own and do not necessarily represent the views of News24.