Technological University Dublin

ARROW@TU Dublin

Dissertations Social Sciences

2019

An Exploration of Managers’ Perspectives on their Role in

Managing Community Early Years Services : Influences and Insights

Jessica Lee

Technological University Dublin

Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/aaschssldis Part of the Social Justice Commons, Social Statistics Commons, and the Social Work Commons

Recommended Citation

Lee, J. (2019)An Exploration of Managers’ Perspectives on their Role in Managing Community Early Years Services : Inf luences and Insights.Dissertation, Technological University Dublin.

This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Social Sciences at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has

been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more

information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected],

[email protected].

TU Dublin – City Campus Online Dissertation Copyright Policy

The TU Dublin City Campus Library Online Dissertation Collection is comprised of undergraduate and postgraduate taught dissertations.

The copyright of a dissertation resides with the author. All TU Dublin students are bound to comply with Irish copyright legislation during their course of study. A dissertation is made available for consultation on the understanding that the reader will not publish it in any form, either the whole or any other part of it, without the written permission of the author.

To learn more about copyright and how it applies to you click here:

The Online Dissertation Collection is only available to be accessed by registered TU Dublin City Campus staff and students. Non-members of TU Dublin cannot be given access to the Online Dissertation Collection. (Please note that this also applies to graduates of TU Dublin and graduates of the former Dublin Institute of Technology requiring a copy of their own work). In using the Online Dissertation Collection students should be fully aware of the following points:

• Usernames and passwords are for personal use only. They must not be divulged for use by any other person.

• The Online Dissertation Collection is provided for personal educational purposes to support you in your courses of study. Use of this collection does not extend to any non-educational or commercial purpose.

• You must not email copies of any dissertation or print out copies for anyone else. You must not under any circumstances post content on bulletin boards, discussion groups or intranets etc.

• You must not remove, obscure or alter in any way any copyright information or watermarks that appear on any material that you download/print from the collection.

TU Dublin City Campus Library has to right to temporarily or permanently remove a digitised dissertation from the collection.

An Exploration of Managers’ Perspectives on their Role in Managing Community Early Years Services:

Influences and Insights

by

Jessica Lee

Submitted to the Department of Social Sciences, Technological University of Dublin in partial fulfillment of the requirement leading to the award of Masters in Mentoring, Management and Leadership in the Early Years

Supervisor: Jan Pettersen

School of Languages, Law and Social Sciences

April 2019

Declaration of Ownership

I hereby certify that the material which is submitted in this thesis towards the award of Masters in Mentoring, Management and Leadership in the Early Years is entirely my own work and has not been submitted for any academic assessment other than part fulfillment of above-named award.

Signature of candidate:

_________________________________________

April 2019

Wordcount: 13,974

Abstract

This exploration into the perspectives of managers of community Early Years services stems from the absence of a requirement of a qualification for supernumerary managers in Early Years services in Ireland and the resulting ambiguity of defined functions of such managers and contextually specific requirements. The aim of the study is to gain a deep insight into the perspectives of the participants on their roles in leading and managing their services. The objectives are to understand what internal and external factors have shaped their roles, to locate the dichotomies and harmonies between what is contextually required of managers and what the true reality of a manager’s role is, and to understand how managers perspectives influence the quality of their services. Grounded theory and social constructivism form the theoretical framework for the research, which is qualitative in its design. In-depth semi-structured interviews were conducted with six managers of community Early Years services in Dublin, Ireland. The findings highlight the key roles and functions of the participants, the factors that influence this, the degree to which each factor is influential, and how this impacts on their service. Additionally, the findings outline the participants’ perspectives on networking, staff and change management, advocacy and the impact that these functions have on their emotions. A key implication of the findings is the significant impact that the participants’ roles had on their emotions, and in turn, the impact of these emotions on their service and how they carry out their roles. Recommendations for the future include development of training for managers in emotional intelligence, the need for provision of networking supports at policy level and further research from the perspectives of managers across the private and community EY sector in Ireland, particularly relating to emotional intelligence and its impact on managers roles, perspectives and quality of their services.

Key words: managers, perspectives, roles, emotional intelligence, networking, grounded theory, social constructivism, quality, leadership, management, early childhood education

Acknowledgements

I kindly acknowledge the academic staff of the Masters in Mentoring, Management

and Leadership in the Early Years, the lecturers and visiting scholars, who enriched

this program with their knowledge and prepared me for the completion of this

program.

I wish to particularly thank Jan Pettersen, the programme chair and my supervisor

during the completion of this thesis, for his time, support, guidance and

encouragement. His invaluable insights, expertise and constructive suggestions were

instrumental in the completion of this thesis.

I wish to express my gratitude to the service managers who participated in this study.

They gave of their valuable and limited time and provided instrumental contributions,

without which, this thesis would not have been possible.

I also wish to acknowledge my fellow students on this program who shared the

journey with me. We laughed, we cried, and we bolstered each other throughout the

entire process. I have made friends for life, for which I am truly grateful.

My final thanks extend to my family and friends, whose support and encouragement

was immeasurable, particularly my husband Gerard. Words can never describe the

unending support and complete lack of complaint during my constant absence while I

carried out research and worked in the library over the last two and a half years.

Thank you to my whole family for your faith in me and your unconditional love.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Declaration of Ownership

Abstract

Acknowledgments

Table of Contents

List of Tables and Figures

Glossary of Key Terms

List of Acronyms

List of Appendices

Chapter 1: Introduction and Background

1.1 Introduction

1.2 Contextual Information

1.2.1 Managing and leading

1.2.2 Policy context

1.3 Rationale for the Study

1.4 Aim and Objectives

1.5 Outline of the Study

1.6 Summary

Chapter 2: Literature Review

2.1 Introduction

2.1.1 Overview of the chapter

2.1.2 National and international context

2.2 The Influence of Policy

2.2.1 Irish regulatory framework

2.2.2 Irish policy framework

2.2.3 International policy framework

2.3 Management in Early Years Services

2.3.1 Contextual factors

2.3.2 The role of the manager

2.3.3 Supervision

2.3.4 Empirical research from the perspectives of managers

2.4 The Influence of Emotions

2.4.1 Emotionality

2.4.2 Communication and emotional intelligence

2.5 The Influence of Managers’ Networks

2.5.1 Networks in the Irish context

2.5.2 Networks in the international context

2.6 Managers as Catalysts for Quality

2.6.1 The effect of competent managers on quality

2.6.2 Quality and management training

2.6.3 Management functions that influence quality

2.7 Summary

Chapter 3: Methodology

3.1 Introduction

3.2 The Research Paradigm

3.3 Research Questions

3.4 Overview of Methodology

3.5 Theoretical Framework

3.5.1 Social constructivism

3.5.2 Grounded theory

3.6 Ethical Considerations

3.6.1 Ethical approval

3.6.2 Informed consent and participation

3.7 Sampling

3.8 Data Collection

3.8.1 Pilot study

3.8.2 Interviews

3.8.3 Context of data collection

3.9 Data Analysis

3.10 Reflexivity

3.11 Methodological Limitations

3.12 Summary

Chapter 4: Presentation of Findings

4.1 Introduction

4.2 Managers’ Perspectives of their Role

4.2.1 Perspectives on administrative tasks

4.2.2 Perspectives on staff management

4.2.3 Perspectives on managing change

4.2.4 Perspectives on staff advocacy

4.3 Influences on Managers’ Perspectives

4.3.1 Emotions

4.3.2 Networks

4.3.3 Managers’ backgrounds

4.3.4 Policy

4.3.5 Theory

4.4 Linking the Manager’s Role to Quality

4.5 Summary

Chapter 5: Discussion of Findings

1 Introduction

5.2 The Influence of Emotions on Managers’ Perspectives

3.2.1 Overview

5.2.2 Administration and managers’ emotions

5.2.3 Staff management and managers’ emotions

5.2.4 Networking and managers emotions

5.3 The Influence of Managers’ Backgrounds Quality of Services

5.3.1 Training and qualifications

5.3.2 Experience

5.3.3 Managers as catalysts for quality

5.4 Summary

Chapter 6: Conclusion and Recommendations

6.1 Conclusion

6.2 Recommendations

6.2.1 Training

6.2.2 Policy

6.2.3 Research

References

Appendix 1: Letter of Information

Appendix 2: Informed Consent Form

Appendix 3: Interview Guide

Appendix 4: Participant Quotations (linked to Chapter 4)

LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES

List of Tables

Table 1: Profile of participants’ services

List of Figures

Fig. 1: Managers’ roles, as perceived by the participants

Fig. 2: Units of influence on a manager’s role, as perceived by the participants

GLOSSARY OF KEY TERMS

Aistear Early Childhood Curriculum Framework, Ireland

Community service Early Years Service in Ireland that is not privately owned / not for profit

Director Formally appointed responsible person in Australian services

Emotionality The physical and behavioural manifestation of emotions

Manager Formally appointed responsible person in Early Years Services in Ireland

Pobal Provides funding of ECCE, CCS, CSSP, CSSRT and AIM schemes in services and is responsible for associated monitoring and inspections on behalf of the Department of Children and Youth Affairs, Ireland

Regulations Child Care Act 1991 (Early Years Services) Regulations 2016, Ireland

Siolta National Quality Framework, Ireland

Staff Team of educators in Early Years Services

Supernumerary Member of staff not included within ratios / does not work directly with children

Tusla The Child and Family Agency, Ireland – provides funding to Community Early Years Services included in the study and carries our inspections of services under the Child Care Act 1991 (Early Years Services) Regulations 2016

LIST OF ACRONYMS

ACECQA Australian Children’s Education & Care Quality Authority

CCS Community Childcare Subvention

CE Community Employment

CECDE Centre for Early Childhood Development and Education

DCYA Department of Children and Youth Affairs, Ireland

DES Department of Education and Skills, Ireland

ECCE Early Childhood Care and Education (free preschool year scheme)

ECE Early Childhood Education

EPPE Effective Provision of PreSchool Education

EY Early Years

EYS Early Years Service

GT Grounded Theory

NCCA National Council for Curriculum and Assessment

NQS National Quality Standards

OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

OFSTED Office of Standards in Education, UK

QQI Quality and Qualifications Ireland

SC Social Constructivist (theory)

T.U. Dublin Technological University, Dublin

UK United Kingdom

US United States (of America)

LIST OF APPENDICES

Appendix 1:

Letter of information

Appendix 2:

Informed consent form

Appendix 3:

Interview guide

Appendix 4:

Participant quotations (linked to Chapter 4)

Chapter 1: Introduction and Background

1.1 Introduction

This research study explores the perspectives of managers of community Early Years Services [EYSs]. This locates the topic within the current context of the Early Years [EY] sector in Ireland and presents the rationale for the study, followed by the provision of contextual and background information. The aim and objectives of the study will then be presented. A brief overview of each chapter will be outlined.

1.2 Contextual Information

Due to the extensive discourse in the literature relating to the concepts of management and leadership, it is important to clarify the utilisation of the term ‘manager’ within this study. For further clarity, as the participants in this study function in contextually differing communities and services and have varying backgrounds in relation to training and experience, it is important to illuminate the underpinning policy context and training provision for EY managers that exists in Ireland.

1.2.1 Managing and leading.

The terms ‘management’ and ‘leadership’ are often used interchangeably to describe positions and roles of power, responsibility, influence and accountability in the EY sector (Dunlop, 2008). There is a vast array of literature discussing either or both, and their overlaps and distinctions. They have been described as distinct components (Rodd, 2006), complementary components (Dunlop, 2008), or inextricably amalgamated (Moyles, 2004). Despite this, it there is an overall acceptance that as there is a significant requirement of both in the EY sector (Price & Ota, 2014). For the purpose of clarity, and considering the limited scope of this study, this chapter will focus on the individual that holds the formal position of manager of an EY service in Ireland and will assume that he/she occupies the dual role of managing and leading the service.

1.2.2 Policy context.

An EYS manager is described in the Child Care Act 1991 (Early Years Services) Regulations 2016 as the “registered provider” who has “day-to day charge of the service” (Department of Children and Youth Affairs [DCYA], 2016,

p. 6). While this description is ambiguous at best, it is reflective of the all encompassing nature and general ambiguity of the role in the Irish context; that a manager has “ultimate responsibility” (Moloney & Pettersen, 2017, p. 86) for all elements of service provision.

Due to the challenges experienced by Australian directors in balancing a dual role of service management and pedagogical leadership, the separation of these two roles into two different individuals was introduced in 2009 (Clarke, 2017; Sims, Waniganayake & Hadley, 2017). As no such legislation exists in Ireland, and as the quality of pedagogical leadership and management is one of the four areas of practice under which EYSs are inspected (Department of Education and Skills [DES], 2018), managers in Ireland must typically assume this dual role. Although McDowall Clark proports that leading quality improvement in EYSs is not contingent on holding the position of manager (2012), for the purposes of this study, ‘manager’ will represent EY leaders that hold the formal position of manager.

A further policy that shapes the EY sector in Ireland is the provision of Higher Capitation funding to services that employ educators with a minimum of a Quality and Qualifications Ireland [QQI] Level 7 qualification (DCYA, 2018). This is influencing the uptake of degree programs by educators in Ireland, however such professionalisation of the sector may not include supernumerary managers, as this increased funding only applies to staff working directly with children.

1.3 Rationale for the Study

In the Irish policy context, there is a distinct focus on educators in ECE in relation to their roles, responsibilities, qualification requirements, professionalism, quality standards of practice, and training and support. However, there is little policy focus on managers, despite extensive empirical research linking effective management and leadership in Early Childhood Education [ECE] to the provision of quality services (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD], 2012; Richards, 2012; Sims, Forrest, Semann and Slattery, 2014; Sylva, Melhuish, Sammons, Siraj Blatchford & Taggart, 2004). It not only imperative, considering the rapidly changing nature of the EY sector in Ireland, that this link is recognised, but that the true reality of the managers role is revealed.

Moreover, this study, will complement Moloney and Pettersen (2017), which focused on managers of both private and community full day services in Ireland. Whenconsidering the findings of both studies, the reader is exposed to a more representative portrayal of the Irish EY sector.

Conducting qualitative research that facilitates the expression of the managers’ own perspectives and how they are influenced will shed light on what local supports and national policies are required to ensure that managers can carry out their roles towards the pursuance of the highest quality for all stakeholders. The findings will seek to draw attention to considerations for research on a greater scale and, consequently, potential improvement in future policy development in Ireland.

1.4 Aim and Objectives

The aim of the study is to gain a deep insight into the perspectives of the participants on their roles in managing their services. The objectives are as follows:

- To understand the internal and external factors that have shaped their roles. – –

- To locate the dichotomies and harmonies between what is required of managers and what the true reality of a manager’s role is.

- To understand the influence of managers perspectives on quality.

The research questions will be outlined in Chapter three.

1.5 Outline of the Study

Chapter two presents an analysis of the relevant research and literature on the topic of managers and their perspectives on their roles, as well as examining literature, both in the Irish and international contexts, in relation to management, leadership, influences on managers perspectives and the impact of management on quality. The theoretical framework will be briefly identified in this chapter and will be explored in detail in Chapter three.

Chapter three presents the research questions and outlines the processes undertaken to collect the data. It will also discuss the paradigm within which the research is located, the theoretical framework that structures and guides the study and the methods utilised. It will then outline the ethical considerations, sampling, data collection and analysis, and methodological limitations. The chapter will conclude with a consideration of reflexivity.

Chapter four will present the findings that emerged following the analysis of the data. The data is collated within categories, based on the most prominent findings. Deviant cases are outlined in addition to the prominent findings. Two models that were developed based on the findings, within the framework of grounded theory, are also presented. It is important to note that, due to the in-depth nature of each interview and the resulting data, lengthy quotations are contained in Appendix 4.

Chapter five will interpret and analysis the findings in the context of the literature and research pertaining to the topic of the study and the research questions. New understandings and insights emerging as a result of the findings will be explained. The significance of the findings will also be outlined Chapter six will synthesise the overall conclusions drawn from this study as well as presenting recommendations in relation to policy and research.

1.6 Summary

This chapter outlined the contextual framework for the study, drawing attention to the utilisation of the concept of management in the study, and the relevance of the study in the Irish EY sector. Additionally, the aim and objectives were outlined. The structure of the chapters contained in this dissertation was also provided. The following chapter will analyse extant literature relating to the topic of the study and its aim and objectives.

Chapter 2: Literature Review

2.1 Introduction

2.1.1 Overview of the chapter.

This chapter will begin by outlining management in EY in Ireland in relation to who occupies management positions and what this role entails. Empirical research focusing on managers’ perspectives will be analysed in relation to this study. The influence of policy and regulation, both nationally and internationally, on managers’ perspectives on their roles will be considered. Internal influences will also be explored, including emotionality,

emotional intelligence and communication. The importance of professional networks is discussed and how this links with managers’ emotionality. Competencies, functions and professional and educational backgrounds of managers will be outlined and how these influence managers. Finally, the concept of managers as catalysts for quality will be explored, and how their perspectives effect this.

2.1.2. National and international literature.

Moloney and Pettersen (2017) is the only research conducted in the Irish context in relation to managers’ roles and their perspectives. Dimmock (2007) reminds us that there has been limited focus on utilising research cross-culturally in management and leadership, which is significant, as the same evidence base often informs policy internationally. As Australia and Ireland both share a policy focus on children over the age of three and a similarly “mixed market” of service types (Moloney & Pettersen, 2017, p. 14), Australian research will be drawn upon. The United Kingdom [UK] sector is considered, however it is acknowledged that all EY provision in the UK falls under the Department for Education [DfE] (DfE, n.d.), whereas such responsibility is divided between multiple departments in Ireland. Research from New Zealand is included, as Aistear, Ireland’s Early Childhood Curriculum Framework, was heavily influenced by New Zealand’s Te Whāriki (French, 2013). As Finland is acknowledged as leading excellence in ECE (OECD, 2016; OECD 2017) and research therein offers alternative insights, it will be referred to. Additionally, research from the United Stated [US] will be presented, owing to its strong focus on EY management policy.

2.2 The Influence of Policy

2.2.1 Irish regulatory framework.

Chambers (1997) states that “many professionals seem driven to simplify what is complex and to standardize what is diverse” (p. 42), a sentiment that remains today in the Irish context (Moloney & Pettersen, 2017). This is referred to by Moloney and Pettersen as a “legislative quagmire” (2017, p. 5). In a review of occupational roles in the sector in Ireland, Urban, Robson and Scacchi (2017) concur by stating that a non-contextualised universal approach will lead to management practices that are inappropriate for the complexity of the Irish EY sector. What conflates this issue is the saturation of literature that attempts to identify generic management strategies (Penn, 2011) thus making it challenging for contextual adaptation.

There are two key sets of criteria under which EYSs in Ireland are inspected that pertain to management. The first is the Early Years Focussed Inspections (Department of Education and Skills, 2015), which include management and leadership for high quality learning as one of four key areas. The second is the Child Care Act 1991 (Early Years Services) Regulations (DCYA, 2016).

The Report on the Quality of Preschool Services (Hanafin, 2014) found that 46.2% of services were non-compliant in governance and management under Regulation 8 of the Child Care (Pre-School Services) (No 2) Regulations 2006 (Department of Health and Children, 2006). This contributed to the commencement of the revised regulations and subsequent inspections, which emphasised management (DCYA, 2016). This has led to an increase administrative burden for managers (Moloney & Pettersen, 2017). Despite the embedding of management and leadership in the regulations, there is little policy provision to equip managers with the necessary resources to carry out their roles effectively.

2.2.2 Irish policy framework.

There are two national frameworks in Ireland under which educators working directly with children build their practice and skills.The first is Aistear: The Early Childhood Curriculum Framework, which provides guidance for educators to enable children to grow as confident and competent learners (National Council for Curriculum and Assessment [NCCA], 2009). The brief reference to management within Aistear is that management is one of two elements of all educators’ roles (NCCA, 2009), which suggests an inaccurate assumption that managers usually work directly with children.

Siolta is the National Quality Framework, which supports educators in defining, assessing and supporting the improvement of quality practice in their own services (Centre for Early Childhood Development and Care [CECDE], 2006; DES, 2017). Siolta Standard 10: Organisation (CECDE, 2006) is based upon management and leadership research from an international context (Rodd, 2006) and only utilises Irish literature that is limited to individual service policy development.

2.2.3 International policy framework.

Leadership and management is one of seven key indicators of quality in the Australian National Quality Standards [NQS] (Australian Children’s Education & Care Quality Authority [ACECQA], 2017a), for which there is a plethora of guidance and resources. It also acknowledges the contextual and local nature of EYSs, therefore mandating continuous reflection, development and improvement. The lack of such detailed guidance and support in Irish policy is glaring. While both Irish frameworks are situated in evidence-based research, they do not emphasise the significance of effective management for quality outcomes for children, nor do they provide guidance for managers that parallels the robustness of the guidance for educators who work directly with children.

Contrarywise, in Finland, where a degree is a qualification requirement, high quality management flourished without direction and monitoring by policy-makers (Sahlberg, 2013). Sims et al. (2014) concur by arguing that EY managers are disempowered by leadership training, as it supports them in following the national discourse surrounding quality, rather than facilitating development that is contextually situated. Such discourse may prioritise compliance, as opposed to enabling debate and reflection in order to develop alternative and contextual ways of achieving quality (Ishimine, Tayler & Thorpe, 2009; Cumming, Sumsion & Wong, 2013).

2.3 Management in Early Years Services

2.3.1 Contextual factors.

Waniganayake, Cheeseman, Fennech, Hadley and Shepherd (2012) assert that management roles within EYSs must be considered in relation to the individual occupying the role, the position that they occupy, and the organisational setting. Moloney and Pettersen (2017) explain that EY managers focus internally towards families, children and educators (micro-system), and externally towards inspectors, funders, quality development organisations (meso-system), legislators, regulators and policy-makers (macro-system). This study is concerned with exploring the influences on managers perspectives, which is closely linked to Bronfenbrenner’s Ecology of Human Development model (1979) and reflects the social constructivist [SC] lens. The SC lens, along with Grounded Theory [GT], forms the theoretical framework of this study. SC emphasises that an individual’s construction of meaning is developed through their cultural and historical experiences and interaction with children and staff in an EY service, and is an ongoing and iterative process (Braun & Clarke, 2013). This process, on an individual level, has been linked to reflective practice (Razik & Swanson, 2001). Furthermore, Lambert (2003) asserts that leading and learning are interconnected, and that the manager is an active participant in the social construction of their role. Due to the nature of SC and GT, it significantly framed the methodological approach to this study, therefore will be discussed in detail in Chapter 3.

In relation to the fulfilling of the role of manager, literature outlining the importance of effective management EY, the identification of key skills and attributes of effective leaders (Aubrey, 2007; Callans & Robins, 2009; Moyles, 2004; Rodd, 2006), practical guides for leading and managing EYSs (Hearron & Hildebrand, 2015; Price and Ota, 2014) and their theoretical underpinnings are abundant. As McDowall Clark and Baylis (2012) outline, such a recent surge in literature can be problematic for managers, due to the variety of approaches and understandings of the role that are presented, thus obscuring clarity for managers.

2.3.2 The role of the manager.

Fifteen years ago, Mujis, Aubrey, Harris and Briggs (2004) acknowledged the paucity of research on management in EY, however in recent years there has been a growth in such literature. More recently, there has been strong discourse surrounding the adoption by educators of leadership responsibilities, separate to the formal role of manager. This was conceptualised as distributed leadership almost two decades ago (Waniganayake, 2000). Siraj-Blatchford and Manni (2007, p. 20) clarified this further as “distributed, participative, facilitative or collaborative” paradigms of leadership, which are underpinned by a team’s movement towards a collective vision. Torrance (2013) challenges some of the assumptions about distributed leadership, the two most pertinent for this study being that “every staff member is able to lead” or that “every staff member wishes to lead” (p. 362), which highlights that effective leadership cannot be practiced by all who assume a manager’s role.

In a study carried out in Ireland that focussed on community EY managers (Cafferkey, 2013), the participants were asked to identify the most important components of their role. Motivation of staff (21%), communication with parents (16%) and advocating for children, the community and other stakeholders (16%) were identified as the three most important components (Cafferkey, 2013).

It is important to note that the roles of leading practice and managing the organisation usually exist within one individual (the manager) in Irish services, which Siraj-Blatchford and Manni (2007) and Whalley and Allen (2011) explain is necessary. These concepts which are explored further by Jones and Pound (2008), Miller and Cable (2011) and Murray (2009). Price and Ota (2014) explain that while a leader must know and communicate the vision, and a manager must provide the environment through which that vision can be consistently communicated and worked towards. Conversely, Hearron and Hildebrand’s US guide on managing EYSs specifically prioritises fiscal, organisational, human relations, marketing and personnel management (2015).

2.3.3 Supervision.

The Office of Standards in Education [OFSTED] in the UK (OFSTED, 2009) indicates that supervision of educators is one of the most essential managerial roles for the improvement of quality in practice. Conversely, Dahlberg, Moss and Pence (2007) found that for effective change management, managers must not be restricted by supervision and administration, but must prioritise pedagogy, and must be willing to evaluate, question, challenge and co-construct.

Gray (2010) maintains that only managers should supervise educators. Richards (2012), however, highlights that the manager may not always be the most suitable person. Price and Ota (2014) also caution that managers often find themselves over-encumbered by managerial responsibilities, often at the expense of the pedagogical leadership and supervision. As supervision is a process that requires a significant investment of time, this function may be delegated to other competent staff (Spouse & Redfern, 2000). Such a time commitment may not be afforded by the manager, as illuminated by Aubrey (2011) who outlines reports by EY managers on their lack of time for reflection and evaluation, due to the time spent on administration.

2.3.4 Empirical research from the perspectives of managers. Rodd (1997)

explored the perspectives of ECE educators who were undertaking learning to become managers and leaders in their services. Managing and supervising staff and maintaining contact with parents and other professionals (34.2% and 22.4% respectively) were ranked as the most important responsibilities. This is contrary to Moloney and Pettersen (2017) who found that 47% of managers in Ireland spend most of their time on administrative tasks. Caution must also be exercised when considering Rodd’s (1997) findings as the study was conducted over two decades ago in a sector that is rapidly changing. Aubrey’s (2007) research clearly showed that the organisational context will greatly influence managers’ roles and priorities. EY managers were found spent most of their time engaged in administrative activities (Aubrey, 2007), which mirrors the most recent findings in the Irish sector (Moloney & Pettersen, 2017).

In a more recent study, Ang (2012) evaluated the perspectives of managers following engagement with the National Professional Qualification in Integrated Centre Leadership [NPQICL]. The findings showed that managers perceived training as essential for promoting critical reflection and engagement with change for the provision of high-quality services. The findings, however, were not representative of the initial sample, as they were correlated using data from a low response rate of participants (8% of questionnaires were returned, and the interviews represented 4% of the overall sample). However, the perspectives of managers are valuable, and the study shows that there is a need for further research on this topic.

Preston (2013) interviewed 28 managers in a chain of EYSs to explore the perspectives of managers on their role and the impact this had on their practice. Recurring themes emerged such as the negative implications of a heavy administrative workload, the lack of formal and continuous professional development, and compliance. These themes are reflective of the current climate within the Irish EY sector (Moloney & Pettersen, 2017). Preston (2013), however, stated that management as a role does not fit within the EY context, however it has been agreed throughout literature that effective leadership and management are essential for high quality services. This assertion may present a bias within the research.

McDowall Clark (2012) conducted research involving the conceptualisation of leadership by 28 managers across a variety of EYSs. While the findings of this study concurred with the low-confidence levels of managers, it is important to note that this cannot be generalised to the EY sector, as the sample was small, and all participants were degree graduates, which is not reflective of the Irish EY sector. The gender balance of participants, however, mirrored that of the Irish sector.

2.4 The Influence of Emotions

2.4.1 Emotionality.

Siraj-Blatchford and Hallet (2014) identify a presence of emotional drive that is unique to those working in the EY sector, which Aubrey (2011) describes as “emotional investment” (p. 56). Rodd (2013) acknowledges that managers must be continually responsive to the needs, problems, demands and expectations of staff, families and other stakeholders, which often elicits emotional responses in the managers. Taggart (2011) notes that emotionality can be perceived as innate to a sector that is predominantly female, which may lead to assumptions of low intellectualism and unprofessionalism. Despite Osgood’s similar findings that outline the dominant discourse surrounding professionalism in management being underpinned by rationalism, without space for emotion, she states that this falls short of the realities of managers in EY (2011). This is also explained by Sevenhuijsen (1998), who, like Urban et al. (2017) and McDowall Clark and Murphy (2012), proposes that such characteristics of managers such as empathy, compassion, intuition and relationality are central to effective leadership, particularly in the EY sector. Osgood (2011), however, cautions that managers must ensure a balance between the utilisation of emotions and potential emotional burnout. Rodd (2013) suggests that supportive strategies must be put in place to counteract this and to ensure emotional intelligence, which Goleman (2006) highlights as an important competency for a manager to possess in order to work with staff towards a shared vision.

2.4.2 Communication and emotional intelligence.

In conjunction with emotional intelligence, Siraj-Blatchford and Hallet (2014) refer to reciprocal and respectful communication as an essential practice of successful EY managers. This skill is underpinned by the ability to act in an emotionally intelligent manner (Rodd, 2013). Considering the social constructivist nature of this study, Chu (2014) describes humans’ predisposition to mirror the emotional state and sometimes physical actions of those in our environment. Self-examination and reflection on strategies such as communication is outlined by Nolan (2008) as a competency present in successful managers. Davis and Ryder (2016) elaborate on this by suggesting that reflecting on his/her emotions enables managers to separate his/her emotions from the influence of the emotions felt by others, thus supporting positive outcomes.

2.5 The Influence of Managers’ Networks

Aubrey (2007) and Robins and Callan (2009) emphasise the importance of cultivating long-term relationships and systems of support between managers in EY, particularly for advice and support. Briggs and Briggs (2009) identify networking as a central element in the development of transformational leadership.

2.5.1 Networks in the Irish context.

In Ireland, the only formal interorganisational networking opportunity for community EYSs is the National Childhood Network [NCN]’s networking initiatives (NCN, n.d.). Despite the outlined success of these initiatives, including improved outcomes for providers and children, increased support and strengthened advocacy, networking is not prioritised in Irish policy. Selden, Sowa and Sandfort (2006) describe formal networking relationships as “interorganizational relationships” (p. 412) and note that they are not commonplace in the EY sector, despite the sector being “fertile ground” (p. 415) for such relationships due to its fragmented nature.

2.5.2 Networks in the international context.

In literature relating to management and leadership in EY in the Irish context, there is little reference to

networking, whereas it has been prioritised in EY sectors internationally. Bloom and Bella (2005), in the US, and Thornton, Wansbrough, Clarkin-Phillips, Aitken and Tamati (2009), in New Zealand, outlined that networking is the most effective tool for developing leadership skills in EY managers. In 2018, the Early Years Network was launched in the UK to encourage professional support and advocacy (Gaunt, 2018). In Australia, a resource kit has been made available to services to develop and sustain professional networks (Western Australia Council of Social Service [WACSS], 2016). In a Finnish study, Hujala and Eskelinen (2013), stated that a focus on networking and collaboration, rather than individual development, is key to developing the EY sector. Within their study, it emerged that Finnish EY managers spent an average of 8% of their time engaging in networking and that networking is prioritised by managers as the third most important aspect of their role and promotes the quality of service provision.

2.6 Managers as Catalysts for Quality

2.6.1 The effect of competent managers on quality.

Notwithstanding the challenges arising from the saturation of literature on management, when considering the role of managers in the pursuance of quality provision, the research is clear. It is an undisputed assertion that the improvement of quality of service provision for children and families is inextricably to the effectiveness of EY managers (Richards, 2012). As previously explored, the de-incentivisation of managers from attaining higher qualifications directly impacts on service quality (Sylva et al., 2004). Additionally, as the managers’ expertise is understood to be a mediating factor in service quality (OECD, 2011; Sims et al., 2014), the limited training and preparation for managers in undertaking their role is linked to quality levels. This may account for the diversity of perspectives that managers have on their roles and how this shapes the overall service.

Urban et al. (2017) remind us that ECE graduates are increasingly questioning how they are to act as leaders and agents of change within management roles, while the sector is characterised by experienced yet lower qualified staff. Critical reflection and systemic thinking must be incorporated into professional development for long standing educators (Osgood, 2008) in order to ensure a collegial space within which a manager can inspire change and drive the quality agenda with a motivated team that is open to change.

2.6.2 Quality and management training.

Educators who receive appropriate training in management have a significant impact on the quality of their service (Hadfield et al, 2012). A shared vision of professionalism across management in the sector, and a collective knowledge of effective practice, knowledges, skills and behaviours will drive forward the agenda of quality development. A study that was conducted on educators in the UK who acquired Early Years Professional Status (advanced training in leadership, management and pedagogy) found that 87% of participants had increased confidence in their leadership skills and 80% reported higher confidence in overall quality improvement of their service (Hadfield et al., 2012).

The reluctance of educators to assume management roles has been widely documented (Dunlop, 2008; Mujis, Aubrey, Harris & Briggs, 2004; Rodd, 2013; Torrance, 2013; Waniganayake, 2014). Mistry and Sood (2012) found that many educators were averse to management roles, as they removed them from working directly with children. Mulligan (2015) adds that this is due to policy requirements such as administrative commitments, governance and financial management. Sims et al. (2014) note that many highly qualified educators find themselves in management accidentally, therefore learn without formal support or training, which Ang (2002) and Dunlop (2002) emphasise as essential.

This was highlighted in Australia in the 1990s (Rodd, 1998; Waniganayake, Morda & Kapsalakis, 2000), which Waniganayake (2014) asserts continues today. McDowall Clark (2012) notes that managers, in the UK, are often recruited with limited theoretical or practical management and leadership expertise, which he attributes to a growth in market-led provision, reflective of Ireland. Lack of interest, low self confidence and inadequate financial remuneration were cited by Rodd (2006) and Waniganayake (2014) as factors that deterred educators from becoming managers. In the US, Bella and Bloom (2003) found that their research participants consistently reflected on the training as empowering and boosting their self-confidence, which transformed how they perceived and carried out their roles.

Within the Irish regulations, there is only a requirement for ECE educators working directly with children to be qualified (DCYA, 2016), however there is no such specification for supernumerary managers. Despite this, as outlined by Sims et al. (2014), many ECE graduates are nominated as manager as they are viewed as proficient in working with children but are often ill-prepared for management. Waniganayake (2014) argues that single module on leadership is insufficient for preparing graduates for the complex and multi-faceted role of manager, as is the current provision in degrees of ECE in Ireland.

2.6.3 Management functions that influence quality.

In the Irish context, French (2003) outlines that clear communication, community engagement, financial skills and responsiveness to staff needs are key factors in EY management. Additionally, provision of centre-specific working conditions (Diamond & Powell, 2011) as well as professional support and development for educators (Ackerman, 2006) are integral to the management of high-quality services (OECD, 2012).

Moloney and Pettersen (2017) assert that entrepreneurship and business acumen are essential, as without providing a stable and sustainable service quality cannot be maintained. Urban et al. (2017) characterise management in ECE as uniquely contentious due to the feminised nature of the sector, which was affirmed by Hard and Jonsdottir’s findings (2013). Their study found that when women in leadership adopt stereotypically “masculine” methods of leadership, they are often met with resistance from staff, whereas when they adopt stereotypically feminine approaches, they find it challenging to promote change (Urban et al., 2017, p. 26). This impacts on a manager’s ability or willingness to challenge norms and raise standards of quality.

2.7 Summary

This chapter addressed the concept of management of EY services. It considered contextual factors in Ireland and contextually similar factors internationally. It explored who takes on the role of manager and what that role entails. The suitability of degree qualified educators to manage was considered nationally and internationally. Influences that shape the role of manager internally, externally and nationally were considered. Emphasis was shown in the literature on such internal influences as emotionality and communication. External influences such as policy and regulatory frameworks and professional networks were highlighted as having a significant effect on EY managers. The connection between a manager and service quality was explored, with reference to the managers competencies, functions and backgrounds and how these influence quality. Through an analysis of empirical research, the perspectives of managers in the literature was understood.

The following chapter will present the methodological approach to this study. It will also present, in further detail, the theoretical framework for this study, as it directly influences the methodology. Ethics, reflexivity and limitations will be discussed.

Chapter 3: Methodology

3.1 Introduction

This chapter outlines the qualitative phenomenological methodology utilised in this study. The interpretivist research paradigm will be presented, which forms the overall approach. This will be followed by the research questions, which informed the direction of the study. Additionally, ethical considerations are outlined, in order to ensure that this study is carried out with due regard to its participants.

The theoretical framework of Social Constructivism will be explored, which explains the contextual implications on the participants. Inductive enquiry is a key feature of this study, as the findings will arise from the analysis of the data, as opposed to deductive enquiry. As such, Grounded Theory will be outlined as part of the theoretical framework of the study. Following this, this chapter will describe the sampling, the data collection process and analysis of the data in this study. The limitations of the study and researcher reflexivity are then examined.

3.2 The Research Paradigm

Mukherji and Albon (2018) ascertain that all research is underpinned by a philosophical approach or paradigm. It influences the approach taken by the researcher, the ethical stance of the study and its methodology and is a lens through which the researcher sees the world (Fraser & Robinson, 2004; Hughes, 2010).

Two paradigms underpin most social research: positivist or interpretivist (Kumar, 2014). This study is underpinned by the interpretivist paradigm, which acknowledges that there are many differing, and equally valid, interpretations of reality – realities which are dependent on time and context (Biggam, 2015; Patton, 2015). Therefore, participants’ words, rather than quantifiable numbers (Denscombe, 2014) were focussed on. The research sought to understand the complexity of participants’ meanings, rather than to identify ultimate truths (Walliman, 2011), and was concerned with gaining a deep and contextual insight into the topic (Mukherji & Albon, 2018).

3.3 Research Questions

As stated by Clough and Nutbrown (2012), the research questions not only influence the direction of the study and the field questions, but also the sample size, the types of participants, the scope and boundaries of the study. Denscombe (2014) outlines seven types of research questions (describing/exploring, explaining causes and consequences, evaluating phenomena, predicting, developing good practice, empowerment, and comparison). The primary research question, which aims to describe and explore (Denscombe, 2014) is:

• How do managers in community EYSs view their role?

The subsidiary research questions, which aim to explain the causes and consequences (Denscombe, 2014) of the managers’ perspectives are:

• What factors (external or internal) helped to shape these perspectives?

• Do prescribed requirements and responsibilities of managers (by external forces such as regulations and policies), differ from the true reality of a manager’s role? In what way(s)?

• How is the service affected, in relation to quality, by the managers perspectives?

3.4 Overview of Methodology

The primary task of methodology, as described by Clough and Nutbrown (2012), is to present to the reader, the triangular connection between the research questions, the research methods, and the generated data. Flick (2007) describes methodology as the sum of influences on the research, such as theoretical frameworks, methods and resources; and how these influences shape the steps taken.

Qualitative design, the chosen methodology for this study, is concerned with the understanding of groups or individuals, as opposed to testing theories (Creswell, 2009) which supports the expression of subjective meaning (Bryman, 2012). It is characterised by relatively smaller sample sizes that enable a richness of understanding (Denscombe, 2014). As this study focussed on the perspectives of individual managers, the facilitation of the in-depth exploration of the lived experiences of the participants was imperative. More specifically, a phenomenological approach has been utilised as it focusses on the lived experiences of the individual, or as Denscombe (2014) explains, seeks to understand the “essence” of personal experience through the participants’ eyes (p. 4).

3.5 Theoretical Framework

Studies that fall within the interpretivist paradigm are described as having no requirement for pre-formulated theoretical bases and should strive to construct theory (Patton, 2015). Corbin and Holt (2011) state that a predefined theoretical framework is unnecessary, and often problematic in qualitative research. However, Schwandt (1993) notes that the researcher cannot enter the research process “tabula rasa” (p. 9). Instead, a researcher must be guided by certain frameworks in order to consider available and relevant knowledge (Punch, 2009) and what requires further study. These frames are labelled as “qualitative inquiry frameworks” by Patton (2015, p. 84) and “informally held concepts” by Ravitch and Riggan (2012, p. 19). Patton (2015) outlines sixteen such approaches, two of which were used in conjunction as a framework for the methodology: Social Constructivism [SC] and Grounded Theory [GT].

3.5.1 Social constructivism.

SC, in this study, asks how the managers have constructed their perspectives, and what the consequences of these are. GT asks what theory, emerging from the analysis of data, explains these constructions. SC exemplifies the understanding that human development is socially situated, and knowledge is constructed through interaction with others (McKinley, 2015). Creswell (2014) intertwines SC with the interpretivist paradigm, as he outlines that adherents to this worldview maintain that meanings derived from experiences are “varied and multiple” (p. 8) and encourages researchers to explore complexities of subjective views, rather than a universally held reality.

The researcher’s theoretical stance was that the interactions between managers, internal stakeholders, external stakeholders, networks and training experiences will influence a manager’s perspective. Schwandt’s statement that “atheoretical research is impossible” (1993, p. 7) is relevant, as SC guided the researcher in forming the primary research question, subsidiary questions and field questions, as well as ensuring that the cited literature is reflective of the aim and objectives.

3.5.2 Grounded theory.

As highlighted by Andrews (2012), SC is innately compatible with GT (particularly constructivist GT), which has become a dominant framework in social research (Denzin, 1997; Morse et al., 2009) as many scholars view it as standard practice and “part of the general lexicon in qualitative research” (Charmaz, 2009, p. 127). During the data collection and analysis stage, concepts will arise from the generated data. Glaser and Strauss (1967), the original proponents of GT, proposed it as the generation of new theories. Dey (2004) reminds us that methodologies change and evolve over time, and as such, Gomm (2009) argues that GT is not only the proposal of new theories, but the generating of findings and locating theoretical explanations for those findings – a theory or model that is grounded in data.

Barbour (2014) notes that the concept of GT is consistent with the inductive nature of the coding of qualitative data, however Charmaz (2005) reminds us that no qualitative method can be wholly inductive, as the analysis and interpretation of data is not objective but affected by the researcher’s lens. Therefore, theoretical influences are present before the collection of data, which the researcher will inevitably use as a frame of reference, particularly in GT. Constructivist GT adopts a reflexive stance by locating the self [the researcher] in the realities of the participants (Charmaz, 2005) by acknowledging the theoretical framework that the researcher used as an initial frame of reference, in this case, social constructivism.

3.6 Ethical Considerations

3.6.1 Ethical approval.

Aubrey et al. define ethics as “the moral philosophy or set of moral principles underpinning a project” (2000, p. 156). As the collection of data may be obtrusive or reveal sensitive information (Creswell & Creswell, 2018), it was essential to ensure informed participant consent, in line with the Technological University Dublin [T.U. Dublin]’s Department of Social Sciences ethical guidelines, as outlined in the following section. There is an assumption that when a participant signs the information letter and consent form, they fully understand and accept the information (Mukherji & Albon, 2018). Additionally, ethical approval was sought from T.U. Dublin’s Head of School, prior to data collection. As the participants in this study are also the gatekeepers, additional gatekeeper’s consent was not required.

3.6.2 Informed consent and participation.

Seidman’s eight essential elements of informed consent were chosen to ensure due ethical consideration, seven of which were applicable to this study and were included in the information letter (2013).

1: Invitation to participate: Initial contact via email introduced the researcher and the research project and provided the information letter and informed consent form (see Appendices 1 and 2)

2: Risk: As the identified risk was that participants may feel vulnerable in sharing their perspectives, they chose a location and time that was comfortable for them (Mason, 2003). The collection of data at the site of the participants’ lived experiences is an important aspect of qualitative research (Creswell & Creswell, 2018).

3: Rights: In order to mitigate participants’ post-interview regret in divulging information (Kirsch, 1999), they were assured that they were under no obligation to participate, that they could withdraw at any time (before, during and after interviewing) and that this would carry no penalty.

4: Possible Benefits: The information letter outlined that there would be no direct benefit to the participants. However, it was explained that the study has a potential to benefit the EY sector.

5: Confidentiality: Full confidentiality could not be assured (Piper & Simons, 2011), as the information shared will be read by others (see dissemination below), however, anonymity was assured. All identifying information would be omitted from all transcripts, written work and derivative papers. The interviews were recorded, and the recordings were encrypted on the researcher’s laptop, which is password protected.

6: Dissemination: The researcher’s supervisor, a second supervisor and an external examiner would read the dissertation and that it may be published on T.U. Dublin’s online portal and/or be adapted for an academic journal. It was stated that the recordings and transcripts would be held for up to three years and then be destroyed.

7: Contact Information and Copies of the Form: Contact information for both the researcher and her supervisor were provided, as well as copies of the informed consent form and information letter.

3.7 Sampling

Flick (2007) identifies sampling as a fundamental aspect of every research design. As well as determining which participants will provide the data for collection, sampling also ascertains the degree to which a study involves comparative potential, which is an important element of GT.

As it is not possible to carry out random sampling in interviewing (Seidman, 2013), due to the small number of participants required, non-probability purposefulsampling was used. Purposeful sampling is the selection of participants based on certain criteria (Lochmiller & Lester, 2017). In this study, the only criterion was that participants must be managers of a community EYSs in Dublin. Community EYSs were chosen, as the operational, financial and governance requirements and responsibilities of private owners/providers and community managers differ greatly and inclusion of both is beyond the capacity of this study.

3.8 Data Collection

3.8.1 Pilot study.

Preparation is critical to the success of the data collection (Biggam, 2015) and assists in planning a more significant study (Gomm, 2009). A pilot interview was carried out to ensure coherence and accessibility of language. The pilot interview assisted the researcher in relying less on the interview guide (see Appendix 3) in order to avoid imposing her own interests on the participants. The pilot also highlighted elements of repetition among guiding interview questions. Upon further reflection, the researcher concluded that the inclusion of discussion with the participants on their core values and beliefs surrounding may illuminate where many of their perspectives arose from.

3.8.2 Interviews.

What is studied and how the data can be accessed is influenced significantly by the methods chosen (Flick, 2007). This study consisted of six semi-structured interviews. This method of interviewing, described as “structured conversations” by Cannold (2001, p. 179), was selected as it gave the participants scope to expand upon topics that resonated with them and to voice their own experiences (Punch, 2005). The semi-structured nature of the interviews enabled the researcher to facilitate such expression, while guiding the interview in a direction that mirrored the aim and objectives of the research. Each interview lasted between 55 and 65 minutes.

3.8.3 Context of data collection.

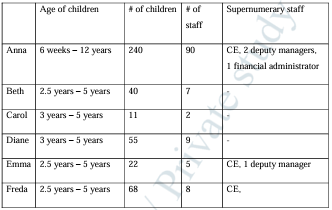

Six community EY managers in Dublin, Ireland were interviewed. For the purposes of maintaining anonymity, each participant was allocated a pseudonym in the transcriptions and in Chapters 4 and 5, as shown in Table 1.

This information was gathered in order to analyse the data in context. This is an important element of qualitative data analysis for the purpose of inductive enquiry, as perspectives are impacted by the experiences of the participants, which is a fundamental element of social constructivism.

Table 1: Profile of participants’ services

The participants’ years in ECE ranged from ten to thirty-eight years, and in EY management from less than one year to thirty-eight years. The qualification levels of the participants ranged from Level 6 to Level 9 in ECE. Three participants received formal training in management, two as part of their ECE qualification (one at Level 6 and one at Level 9), and one as part of a course unrelated to ECE. Despite all services being not-for-profit, each of the participants’ services has contextual variations.

3.9 Data Analysis

Clough and Nutbrown (2012) describe data analysis as the act of reducing something complex into its simplest forms for the purpose of the research aim and objectives. It is important to note, however, that the removal of the superfluous elements was undertaken with caution in order to ensure that all essential elements of the study remained, and that the participants views were represented accurately.

As GT is an iterative process, the first phase of coding used open-coding to identify potential categories by extracting verbatim samples from transcriptions (Ryan & Bernard, 2003). For the second phase, as categories emerge, they are linked together using causation coding, which searches for combinations of variables to map influences. Considering the primary research question and theoretical framework, comparing and contrasting managers’ perspectives was used to link categories (Strauss & Corbin, 1990). Considering the subsidiary questions, which included explaining causes and consequences of the phenomena (Denscombe, 2014), a conditional matrix (Strauss & Corbin, 1990) was generated to illustrate the degree to which the managers’ perspectives were influenced by differing factors. An integrative approach was used, which provides for a small number of predetermined codes (pertaining to the aim and objectives of the research) to be designed, and emerging codes (codes that are developed after data collection, as participants offer their perspectives). Where a deviant case (a contribution that is coded once, but is still valuable) emerged, it was included in the analysis. The codes were then applied in order to establish themes in the participants’ responses and to interpret the data collected.

3.10 Reflexivity

A paramount factor of the interpretivist approach is that the researcher is “inextricably bound into the human situation which he/she is studying” (Walliman, 2011, p. 74). As the researcher is the data collection instrument and, as such, a “potential contaminant” (Fine, Weis, Weseen & Wong, 2000, p. 108), Barbour (2008) remarks that the researcher must acknowledge his/her values and biases during the research process. Reflecting on how the researcher may have influenced the data and vice versa is an important step in avoiding self-delusion, ensuring honesty and demonstrating “methodological frankness” (Miles & Huberman, 1994, p. 294).

As the researcher has read and critically analysed literature concerning the research topic, her view of the research question may differ from that of the participants. Additionally, as all participants have more years’ experience in ECE than the researcher, their perspectives on management may differ. In order to mitigate this and ensure adequate representation of the participants’ perspectives, the researcher ensured that direct quotes were used when analysing the data and discussing the findings.

It was relevant to include questions regarding the participants’ educational and professional backgrounds, in order to highlight the difference in context between each participant, and between the participants and the researcher. Based on the researcher’s background, the guiding field questions may have included some elements that the participants did not feel were important to their perspectives. Additionally, constructivist grounded theory invites the researcher to explore the participants’ past and recent circumstances to understand what influenced their construction of meaning and perspective, without losing sight of the research question(s) (Charmaz, 2009).

3.11 Methodological Limitations

Silverman (2017) notes that some information may not be reported by the participant to the researcher. Furthermore, according to Mason (2003), “vagaries of memory” (p. 237), selectivity and deception by participants are often cited in the literature as criticisms of interview. A participant would likely refer to a variety of points in time, or the culmination of experience over time in order to express what is meaningful to them and their worldview.

A clear limitation of this study, given the qualitative methodology, the relatively small sample size and the fact that such experiences are from the perspective of the participant, the findings cannot be generalised (Greene & Hogan, 2005) but apply only to the participant by whom they were expressed.

A further limitation of this study is the length of time available for its completion, therefore further study is warranted. This may enable a greater number of concepts or themes to emerge, which may reveal pertinent aspects of the EY management sector in Ireland that are beyond the scope of this study.

3.12 Summary

This chapter described the methodological approach (qualitative) through which this study was carried out. The interpretivist research paradigm was presented, as well as the research question and subsidiary questions. Detail on the theoretical framework (social constructivism and grounded theory) of the study was highlighted and critically analysed for its relevance to this research. Ethical considerations were outlined in detail. The sampling process and the collection and analysis of data were described. Considering the validity of this study, reflexivity and limitations of the research were also discussed. The following chapter will present the finding that emerged following the collection and analysis of the data.

Chapter 4: Presentation of Findings

4.1 Introduction

This chapter provides a detailed account of the key findings. Data collected through six in-depth semi-structured interviews is presented and analysed, as described in Chapter 3. This chapter is divided into three sections, which represent the primary categories that emerged during coding. The three categories are as follows:

The managers’ perspectives of:

1. Their role in the service

2. What influences their role

3. How their role is linked to quality

These key categories correlated with the initial research question and subsidiary research questions and were focusses of the interview guide.

Within each category, several subcategories emerged, which will be outlined in the subsections to follow. The first section will examine the participants’ perspectives of their roles, responsibilities and functions. The second section will outline the internal and external influences on the participants’ perspectives and the effects of these on their roles. The third section will analyse the managers’ perceptions of themselves as catalysts for quality. The chapter concludes with a summary of the main points raised through the analysis of data. For further illustration of the key elements of this chapter, additional quotes from the participants can be found in Appendix 4. Links are made between this chapter and the quotations in Appendix 4 by utilising tags containing ‘Q’ and a number in-text. This tag is linked to its corresponding quotation in Appendix 4.

4.2 Managers’ Perspectives of their Role

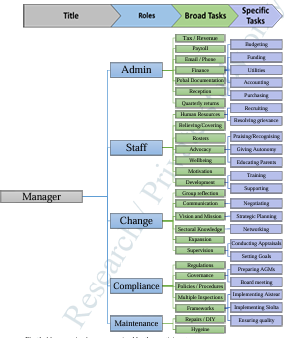

A prominent subcategory that emerged was managers’ perspectives on their roles in relation to administrative tasks. A further recurring subcategory was staff management which included advocating for staff, staff development, valuing staff and empowering them. Overlapping with staff management, change management emerged as a subcategory, specifically supervision, reflective practice and communication styles. Fig. 1 outlines the roles as perceived by the participants.

4.2.1 Perspectives on administrative tasks.

A significant reality of five participants was the time that was required for administrative tasks. Owing to this, the participants could not work directly with children as it would negatively affect the children due to their managerial role distracting them (Q1 and Q2).

Despite Anna having a part-time administrator, she noted that she does most of the financial tasks, as these are a “biggie” for her role. Carol’s role largely requires grant applications while Anna engages in “a massive amount of fundraising”. Emma opted out of the primary community funding scheme (Community Childcare Subvention [CCS]), due to the administrative burden. Freda and Emma both expressed missing working directly with the children, but pressures arising from administrative tasks prohibit this.

Freda explained that, despite wanting to spend time in classrooms, she enjoys administration as it is “straight-forward” and “black and white” although it is all encompassing (Q3). Conversely, Beth explained that she does administrative tasks for one hour per day because, “the children and the rooms will be top priority […] I can always do [the paperwork] at a later stage if it needs to be done”.

Diane and Emma both found sustaining relationships with parents challenging, due to administration. Diane perceived parents as associating her with fees or administration relating to funding schemes, while Emma said, “I am seen as the boss […] They won’t go near me for anything” and Q4.

Unlike Diane and Emma, Beth perceives her role as vital for providing a main contact point for parents, which Freda devotes one hour per day to doing. Interestingly, all participants referred to working closely with both parents and staff as essential, whether their time constraints permitted it.

4.2.2 Perspectives on staff management.

Diane asserted that she does not supervise staff as she has confidence in her staff to resolve challenges independently. In relation to staff development, she observed peer pressure within her team as a motivating factor (Q5).

Like Diane, Anna highlighted the importance of trusting her staff when challenges arise. Unlike Diane, the other five participants spoke at length about both the importance of, and the methods through which, they support staff. Anna advocated for consistent support, training, and even counselling for retaining loyalty and commitment. Anna also reflected on the importance of valuing staff and, like Carol (Q6), being available to them (Q7). Similarly, Beth explained that a manager is “a figure there that they can turn to if necessary and also pick up the slack”, despite her knowledge that her team can work independently, akin to Diane. Diane outlined that the staff don’t “take advantage” of her being in the classroom, as they are aware of the supernumerary requirements of her role.

In relation to valuing staff, Freda described a regulatory inspection of her service, during which the inspector only questioned the degree qualified educator. Freda stressed that all educators are equal partners in the service, regardless of qualifications, and that the educators with lower qualifications, in this case, felt like “second-class citizens”. Anna cited the empowerment of staff as a critical function of her role. She described a time when she enabled the deputy manager to practice her skills in management and enabled Anna to identify areas that needed further support. Beth empowered her staff by ensuring their involvement in all decision-making, as the owners of a service she had previously worked in made all decisions off-site without team input, which she critiqued.

4.2.3 Perspectives on managing change.

Carol, Emma and Anna referred to monthly supervision as key elements of their roles in change management (Q8), in order to set goals (Anna) or to maintain relationships with staff (Emma). Diane, on the other hand, commented that she deems supervision unnecessary, due to the educators being more experienced than she. Freda surmised that there is a supervision imbalance, as managers rarely receive it, which she maintains is important for a manager’s wellbeing (Q9).

Emma described her team as a continuous and capable community of learners. She cited the most effective method of creating a shared vision is adapting her communication style in line with different learning styles. Beth commented that before her commencement, staff were discontented as there was no clear vision. Emma and Beth both advocated that it must be developed and communicated collegially and appropriately. Likewise, in relation to the introduction of Aistear and Siolta, Freda stated that the team faced the challenge together. Conversely, Diane shared an example of managing change in her service in an authoritative manner (Q10).

Akin to Beth and Freda, Emma described how she encouraged a shared understanding of concepts such as play, interactions and frameworks. She challenged her staff’s convictions and biases by encouraging deep reflection on the theory of play (Q11). As well as promoting critical self-reflection, Beth highlighted the importance of a manager’s ability to critically self-reflect. She explained that a manager’s personal perspectives must be reflected on, as she described her former manager who prohibited sand-play because she disliked untidiness.

4.2.4 Perspectives on staff advocacy.

Similar to Carol and Anna valuing staff, Beth described verbally praising at every opportunity and affording ownership over the decisions. She also highlighted how high staff morale positively impacts on children (Q12).

Freda recalled when her team did not feel confident in describing themselves as educators or teachers. As described above, like Beth’s and Emma’s encouragement of self-reflection, Freda’s role then involved counteracting this by asking, “What do you do?”, “What is an educator?” and “How do you get to feel this way?”. Beth also expressed her discontent at what she perceives as a lack of recognition for educators’ qualifications and expertise (Q13).

4.3 Influences on Managers’ Perspectives

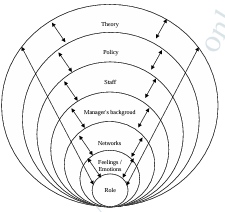

The factors that influenced the participants’ perspectives on their roles most significantly are represented in Fig. 2. The further the distance from the central element of the model in Fig. 2 (‘role’), the lower level of influence the factors exerted over the participants’ roles. As the influence of staff on the participants’ roles was discussed in section 4.2.2, this will not be discussed in this section. The influence of administration was outlined in section 4.2.1, therefore this section will highlight other influential policy aspects. Many of these factors are interconnected and overlap.

4.3.1 Emotions.

The managers’ emotions were cited as the most prominent influence on how the participants’ roles were shaped and how functions were prioritised. Emma felt empathy towards her staff that were re-qualifying, therefore she prioritised supporting these staff (Q14). Beth had felt unsupported in her previous service, within which the manager rarely left the office. “They weren’t approachable. That was hard sometimes”, hence, since becoming a manager, Beth prioritised spending time in the classrooms, supporting the educators.

Carol cited high stress levels due to funding changes, which had resulted in inadequate classroom and hygiene staff. Consequently, Carol works predominantly with the children, spends her spare time cleaning and prioritises sourcing new funding streams.

Diane recalled a staff member that declined to undergo mandatory Level 5 training, which caused high levels of stress for Diane (Q15 and Q16). Anna recalled feeling anxious throughout her services financial difficulties and when she attended court for a child protection case. Subsequently, Anna prioritised sourcing external supports for both her staff and she (Q17).

Similarly, Freda revealed emotionally arduous incidents which affected her confidence: “I thought it was just my management. I thought that I am just not managing this well”. Diane spoke about her need to seek the support of professional networks. All six participants highlighted networking as a key mediator in the emotional wellbeing of managers.

4.3.2 Networks.

Diane’s and Freda’s perspectives were that a manager must prioritise communicating with other managers. Diane stated, “I needed someone to tell me it was going to be ok and not to worry”, while Freda wanted “just to know that you are not the only one”.